ItchySats - Unpacking the CFD protocol

At the end of 2021, we shared with you our plans to create the most awesome Bitcoin DEX. In that post, we outlined how we will take our current solution to the next level over the rest of the year. We also promised to give you a detailed explanation of how our Bitcoin CFDs actually work. Which is why we are here today.

Opening a CFD

You may have seen this screen before if you've used itchysats in the past.

You are about to take an offer from the maker you are connected to.

You click on the button and the UI says that a new CFD is in contract set up.

After a few seconds, the CFD transitions to a new Open state and you can see that a transaction has been broadcast.

Everything seems to be working, but you have no idea what has just happened.

Setting up the contract

Clicking on the button sends a message to the maker telling them that you want to take their CFD with your chosen leverage and specified quantity.

If they accept this request, the applications start the contract_setup: a multi-message exchange of public keys, addresses and signatures which will enable the opening of the CFD.

We refrain from specifying the messages here for clarity, but we encourage you to read the code if you want even more details. Our CFD protocol library lives in a separate repository: maia.

Instead, we will focus on the output of these rounds of communication: the building blocks of our CFD.

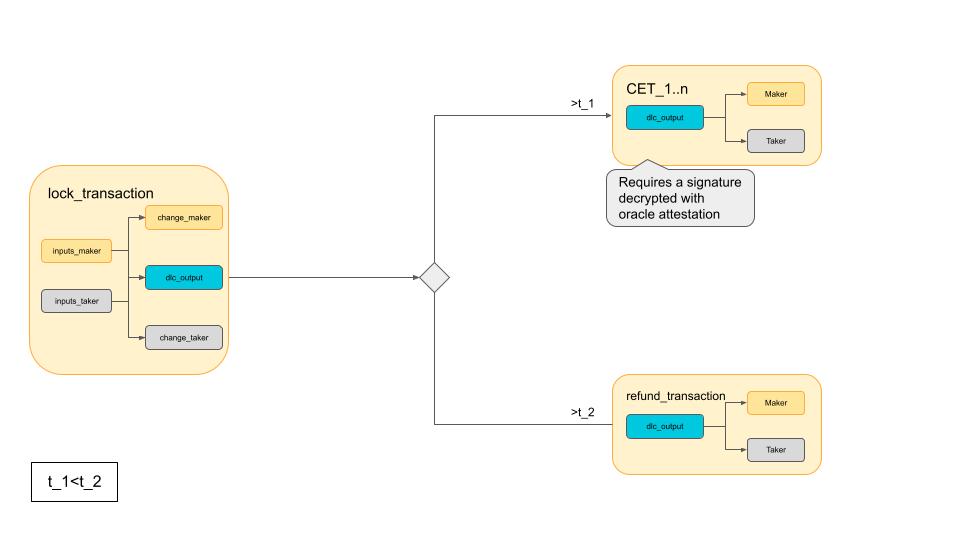

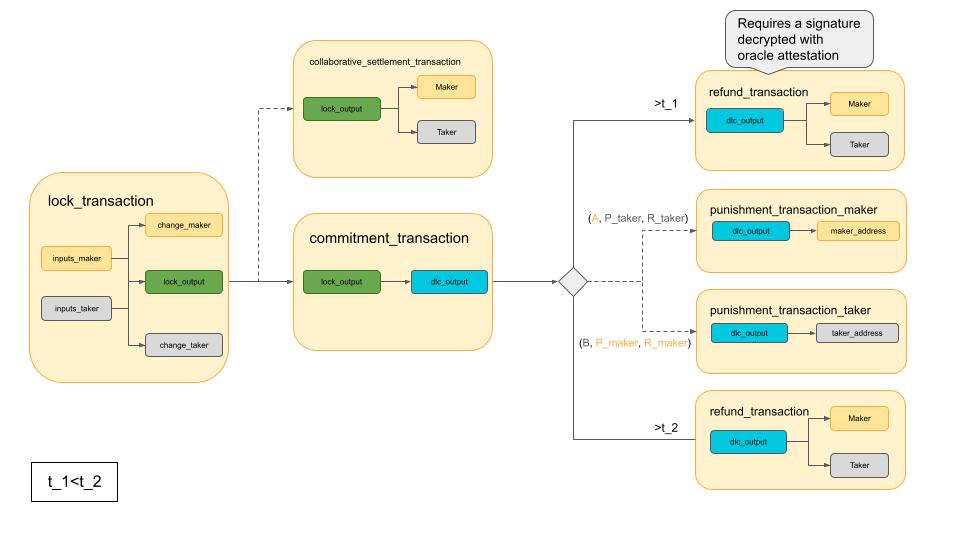

Lock transaction

Both parties involved in the CFD need to lock up some coins on the blockchain, so that the protocol can enforce the outcome of the bet1.

The lock_transaction takes one or more inputs from each party.

It produces a shared output which combines the coins from maker and taker.

We will refer to this shared output as the dlc_output from now on.

We will explain the meaning of that in the next section.

The transaction may also include one or more change outputs per party.

By the end of contract_setup, both parties will have a copy of this fully signed transaction. That is, the maker will have signed all of their inputs and so will have the taker.

Thus after contract_setup either party can immediately open the CFD by broadcasting the lock_transaction.

It doesn't matter who sends it or even if both parties do it: it is the same transaction, so the blockchain will accept the first one and ignore any duplicates.

Either party will still have a chance to back out of the CFD before the lock_transaction is broadcast.

If they spend any of the inputs used in the lock_transaction in a different transaction, the lock_transaction will not be mined, as it would represent an attempt at a double-spend.

The DLC output

As mentioned above, the output of the lock_transaction which is relevant for the protocol is the dlc_output.

A Discreet Log Contract (DLC) is a type of output which is spendable depending on the outcome of an event according to a trusted third party, commonly referred to as an oracle.

It is a mechanism through which transaction spend conditions can depend on events external to the blockchain.

In our case, this is how we can settle the CFD based on the price movement of BTC.

The dlc_output is a simple 2-of-2 multi-signature output on a public key A from the maker and a public key B from the taker.

That is, it requires a signature from the maker and a signature from the taker to be spent.

What makes a DLC work are all the pre-computed transactions which spend the multi-signature output in different ways. A transaction which spends a DLC based on the outcome of an event is referred to as a Contract Execution Transaction (CET). The way the oracle enables the publication of a particular CET stems from the usage of adaptor signatures2. We will show how this works with a basic example.

CETs exemplified

In our example, maker and taker have set up a very simple CFD: if the price of BTC exceeds 40k USD by the end of the contract, the taker wins all the coins; on the other hand, if the price is lower than or equal to 40k USD by then, the maker wins it all.

With only two possible outcomes they only need to create two CETs: one giving all the coins in the dlc_output to the taker and another giving all the coins to the maker.

In order to prevent these CETs from being published immediately after the lock_transaction is broadcast, both parties only share an adaptor signature on each CET under their public key.

These adaptor signatures are constructed in such a way that they can only be decrypted and transformed into regular signatures depending on what price the oracle attests to in the future.

Specific to our example, before we start the contract_setup, the oracle has already announced that it will attest to the price of BTC in USD in 24 hours.

The oracle is identified by a public key O, and it will use the corresponding secret key o to attest to a price using a known attestation scheme3.

The oracle's announcement includes a public key K which represents the oracle's commitment to use the corresponding random nonce k in the attestation of this particular event in the future.

The nonce k is what allows the oracle to attest to infinitely many events over time without needing to change its attesting secret key o4.

With the announcement's nonce public key K, the oracle's attesting public key O and an identifier for the price range that should unlock a particular CET, each party can construct adaptor points which can be used to produce the relevant adaptor signatures that they will share with the counterparty.

For example, the taker uses K, O and an identifier for the range 0-40k USD to produce an adaptor point Y_short.

They then encrypt under Y_short their signature for their public key B on the CET that gives all of the coins to the maker.

During contract_setup they share this adaptor signature with the maker.

The maker will be able to decrypt that signature and publish the corresponding CET if the oracle attests to a price lower than or equal 40k USD.

In practice, the oracle we've integrated5 with, olivia, doesn't attest to an identifier for a price range, nor to a specific price.

Instead, it attests to the binary digits of the price, one by one.

This allows us to reduce the number of CETs that both parties need to build and produce adaptor signatures for during contract_setup.

The example above is a simplification, since in the real world the payouts of a CFD usually follow a smooth curve.

If we were to use exact prices for these, the number of CETs could be extremely high, causing storage and time inefficiencies in the protocol.

The combination of discretising the payout curve into intervals and using an oracle which attests to the individual BTC price bits, means that we can have relatively expressive payout curves without incurring in very long contract_setups and prohibitive space requirements.

The specifics of how this is achieved may come in a future post, but as always we encourage you to take a look at the code and ask questions if you want to learn more.

Refund transaction

In the previous section we indicated that this protocol requires trust on a third party: the oracle.

Even if you split the trust among multiple oracles, you have to prepare yourself for the possibility of too many of them being down when the price attestation is supposed to be published.

With only CETs to spend the dlc_output, our protocol could render these coins unspendable if olivia misses the publication of the attestation corresponding to the announcement used during contract setup.

To prepare for this unlikely situation, both parties work together to construct and sign a refund_transaction during contract_setup.

This transaction spends the dlc_output to outputs that return the coins back to maker and taker, in the original proportion.

A relative timelock is applied to the input of the refund_transaction, ensuring that the transaction will only be mined if enough time has passed since the lock_transaction was published.

The value of this relative timelock is chosen so that both parties have enough time to publish a CET that was unlocked by olivia's publication of the relevant attestation.

Perpetual CFDs

The previous section is a pretty accurate description of the first version of our CFD protocol. Nevertheless, during its implementation we realised that we had another requirement that we had yet to meet: a CFD, by definition, must not have an expiry date.

Now, one cannot easily take a construct from the conventional financial world such as a CFD and reproduce it exactly on the blockchain. We will likely always need pre-defined cutoff points at which either party can settle the CFD unilaterally (by publishing a CET after the attestation time). Without them, an uncooperative counterparty could freeze the funds indefinitely.

But we can still mimic the perpetual nature of a conventional CFD by allowing both parties to agree to renew the lifetime of the contract past the previously determined attestation time.

Rollover

Rolling over a CFD means that we add a whole new set of CETs which depend on an event whose outcome will be attested to further in the future.

The process of constructing these CETs is the same as described above.

Unfortunately, spending directly from the lock_transaction doesn't work.

The original set of CETs that were created during contract_setup would still be perfectly valid, so even though both parties could theoretically refrain from publishing an "old" CET after being unlocked by its corresponding attestation, that would require trusting each other.

Luckily, this kind of problem has been solved in the past, the most prominent example being the Lightning Network's revocation mechanism. Having worked on an implementation of Generalized Bitcoin-Compatible Channels, we knew that we wanted to apply those same constructs to our CFD protocol.

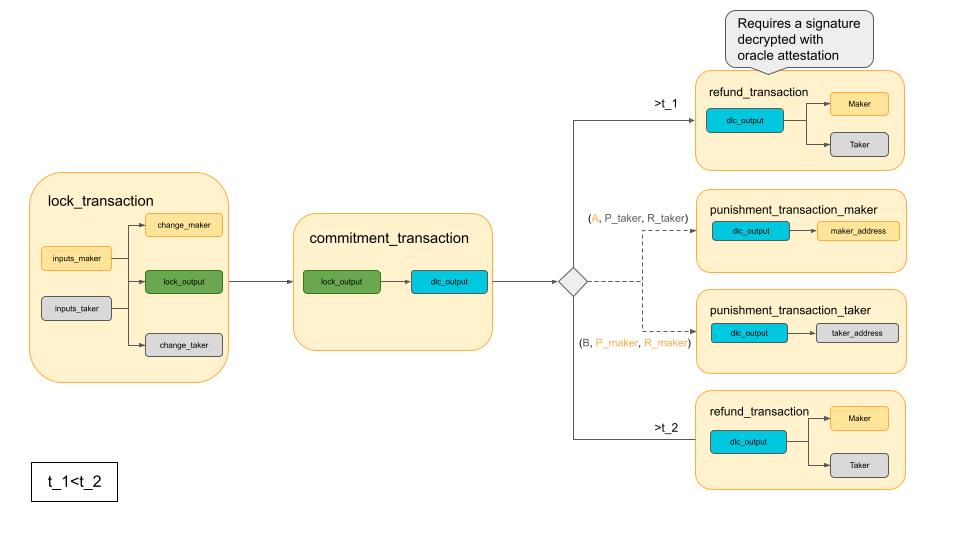

Commitment transaction

The lock_transaction's output is now fittingly referred to as the lock_output.

Its purpose is only to certify the creation of the CFD.

After its publication parties can no longer back out of the contract.

Its output is no longer spent by CETs directly.

Instead, a commitment_transaction is introduced, which spends the lock_output into the dlc_output.

The dlc_output, now part of a different transaction in the protocol, is still spent in the same way described previously: a set of CETs define how the dlc_output is split up based on the price of BTC in USD.

The purpose of the commitment_transaction is to enforce that the dlc_output can only be spent by the CETs which were constructed together with it.

Importantly, the refund_transaction works the same as before: it spends the dlc_output, which is now an output to the commitment_transaction.

We focus on the CETs for clarity, but everything applies to the refund_transaction as was discussed in previous sections.

As an example, we can imagine maker and taker agreeing to roll over the CFD because they're both optimistic that the price movement of BTC will benefit them if they wait longer.

During contract_setup, they created and signed commitment_transaction_0 and a whole set of CETs along with it.

During rollover, they produce a new commitment_transaction_1 and a new collection of CETs based on a new announcement from olivia.

Since they have the means to publish fully signed commitment_transactions, they can eventually publish commitment_transaction_1 and settle the CFD based on a newer attestation from olivia.

Punish transaction

But, what happens if either party decides to publish an old commitment_transaction_0 and settle the CFD based on an old BTC price attested by the oracle?

That would defeat the purpose of rolling over the CFD.

This is where the revocation mechanism comes in.

A commitment_transaction's dlc_output can actually be spent in one more way.

In full, the commitment_transaction can be spent with:

During contract_setup and every subsequent rollover, parties work together to add another spending condition to the dlc_output.

They each generate a revocation keypair (r, R) and a publishing keypair (p, P) and share the public keys with each other.

The dlc_output is no longer a simple 2-of-2 multisig on their public keys A and B.

It also includes:

Instead of exchanging regular signatures on the commitment_transaction, they create one adaptor signature each.

For example, the taker encrypts under P_maker their signature for their public key B on the commitment_transaction.

Later on, the maker can decrypt the taker's adaptor signature using the publishing secret key p_maker.

If they eventually publish the commitment_transaction using the decrypted signature, they leak p_maker to the taker.

Additionally, every time after a contract rollover is completed, both parties must exchange their revocation secret keys.

If one's counterparty does not share the revocation secret key after rollover, they should immediately publish the new commitment_transaction.

Otherwise their counterparty would be able to choose which comitment_transaction to broadcast at any point, giving them the option to select a more favourable settlement.

With all this in place, maker and taker know that they are protected against a counterparty who attempts to publish a revoked (not produced by the most recent rollover or contract_setup) commitment_transaction.

As soon as they spot it on the blockchain, they can learn the other party's publishing secret key p, take the corresponding counterparty revocation secret key r that they learnt after rolling over and construct and sign a transaction which gives them all the coins in the dlc_output.

Obviously, this mechanism imposes an almost-always-online requirement (and a need to store revocation secrets) on both parties after the first contract rollover.

They must be on the lookout for the publication of any revoked commitment_transaction.

There does exist a relative timelock on every CET, so that a cheated party has sufficient time to react with a punishment_transaction.

Collaborating on the blockchain

With what we have presented so far, the CFD protocol is quite usable. The systems in place allow us to imitate the mechanics of a conventional CFD and protect the coins of everyone involved, in a setting such as the blockchain, where you should not need to trust anyone.

But we did identify another limitation that we wanted to mitigate: the inability to close a position at any point in time.

In conventional finance, one is able to close a CFD and take their winnings or losses, whenever they choose to.

With our Bitcoin CFDs, we are limited to those times when the oracle produces an attestation for the price of BTC, corresponding to the announcement used during contract_setup or rollover.

There does not seem to be a way to allow for fully unilateral closing of CFDs, but we have introduced a mechanism through which two parties can agree to close a position earlier than the attestation time.

We have called this collaborative_settlement.

If maker and taker agree to settle the CFD with a particular payout, they work together to create and sign a transaction which spends the lock_output directly.

This does mean that both parties need to be online and agree to effect the early closing of a CFD.

But, if the conditions are not met, both parties know that they can still rely on regular settlement via CET, thanks to the wonders of cryptography.

Looking ahead

While we are proud of the work we've done in putting together this CFD protocol on Bitcoin, we realise that there is more work that can be done. Our roadmap blog post includes some things we will be tackling in the future, but there are other improvements and features that we are considering.

Out of all the things that we have in mind, we think it would be very important to implement CFDs that don't depend on a single oracle. As implied before, protocols based on DLCs demand trust on oracles. But if we can split this responsibility among multiple entities, the likelihood of collusion or even malfunction would be significantly reduced. More specifically, with multiple oracles the settlement of a CFD via CET would no longer depend on a single oracle attesting to some price. Instead, we would use the attestations of multiple oracles to decide on which CET to activate. For example, we could envision a 4-of-7 setup, where a simple majority of oracles agreeing on the same outcome would decide which CET to unlock.

There is ongoing research in this area which we are following closely.

You can follow our progress on the protocol and itchysats in our open source repositories.

We also encourage you to join our public communication channels if you have any questions: Telegram and Matrix.

- At its core, a CFD is a bet on the price of an asset in the future.↩

- Our

dlc_outputpowered by adaptor signatures is based on dlcspecs, a project which is working on a specification for DLCs. It does not follow the original work by Dryja.↩ - The attestation scheme would usually be a signature scheme, such as Schnorr. We actually use a simpler attestation scheme defined by the independent oracle we have integrated with. For more details check out

oliviaand this module inside our CFD protocol library.↩ - Without a nonce or, more commonly, using the same nonce more than once, the oracle would leak its own attesting secret key after attesting to outcomes.↩

- It is important that the oracle is not affiliated with either party involved in the CFD (and a DLC more generally). Otherwise they would be able to interfere with the attested outcome of an event for their own benefit.↩